Picture this scene. It is 2:00 PM. The dive boat is heading back to the marina after a long day at Isla del Caño. You are tired, salty, and happy. The Divemaster brings out a stack of paper logbooks and a stamp. He shouts: “Okay everyone, dive one was 45 minutes, max depth 18 meters!”

Half the divers on the boat roll their eyes. They groan. It feels like homework. They think: “I have a dive computer that records this. Why do I need to write it down with a pen like it is 1995?”

I understand that feeling. In a digital world, the paper logbook feels like a relic. But as an instructor with 15 years of experience, from the warm waters of Thailand to the dark, flooded mines of Europe, I am here to tell you that your logbook is the most underrated piece of safety gear you own.

It is not just a diary for memories. It is a technical database. It is your passport. And sometimes, it is the only thing standing between you and a disastrous dive. Here is why you need to stop treating it like a souvenir and start treating it like a scientific tool.

The Dive Logbook: Technical Data You Forget

The biggest misconception about logbooks is that they are for recording “what you saw.” Yes, writing down “I saw a Manta Ray” is nice for nostalgia. But relying on your memory for technical details is a recipe for failure.

The human brain is terrible at remembering numbers over long periods. You might think you will remember how much weight you used today, but in six months, you will forget. And that small number determines your safety.

The Weighting Trap

Let’s say you dive today in Costa Rica. You are wearing a 3mm shorty wetsuit. You use an aluminum tank. You need 4 kg (8 lbs) of lead to be neutrally buoyant. You feel great.

Six months later, you go to the Canary Islands. The water is colder. You rent a 7mm long wetsuit with a hooded vest. The dive shop gives you a steel tank (which is negatively buoyant). You stand on the boat and think: “How much lead do I need?”

If you rely on your memory, you might say “4 kg,” because that is what you used last time. But with the thicker suit, you will be dangerously underweighted. You won’t be able to descend. Or worse, you will struggle to hold your safety stop at the end of the dive. If you had a logbook, you would look back and see: “7mm suit = 8 kg.” Problem solved.

The “Check-Dive” Shield (Why You Need Proof)

Imagine this: You are an Advanced Open Water diver. You have done 50 dives. You arrive at a high-end dive center in Costa Rica or Mexico, and you want to dive the famous deep shipwreck or the shark caverns.

You walk into the shop and say: “I am experienced. Take me to the best site.”

The first thing the instructor will ask is: “Can I see your logbook?”

If you say: “I don’t keep one,” or “It’s on an app that won’t load,” or you show a digital card that was issued in 2015, we have a problem. As an scuba instructor, I do not know you. I do not know if you are a ninja underwater or a liability. If you cannot prove you have been diving recently, I cannot take you to the advanced site.

The Consequence

I will have to put you on a “Check Dive.” This is usually a shallow, easy dive where I verify your skills. You might have to pay for a private guide, or you might waste a day of your vacation doing a dive that is below your skill level. A well-filled logbook is your proof of currency. It tells me: “This person dived two months ago, handled 30 meters, and had no issues.” It is your VIP pass to the good stuff.

Paper vs. Digital vs. The Computer Memory

The debate is eternal. Should you stick to the classic paper binder, use a smartphone app, or just trust your dive computer’s internal memory?

1. The Dive Computer (The Fallible Backup)

Your dive computer is amazing, but it is not a logbook.

First, its memory is limited. Most entry-level computers (like the Suunto Zoop) overwrite their memory after 40 or 50 hours of diving. If you dive a lot, your history from last year is gone.

Second, it records data but not context. It records “Depth: 20m, Time: 45min.” It does not record “Current was strong,” “I felt cold,” or “My mask leaked.” Without context, data is useless.

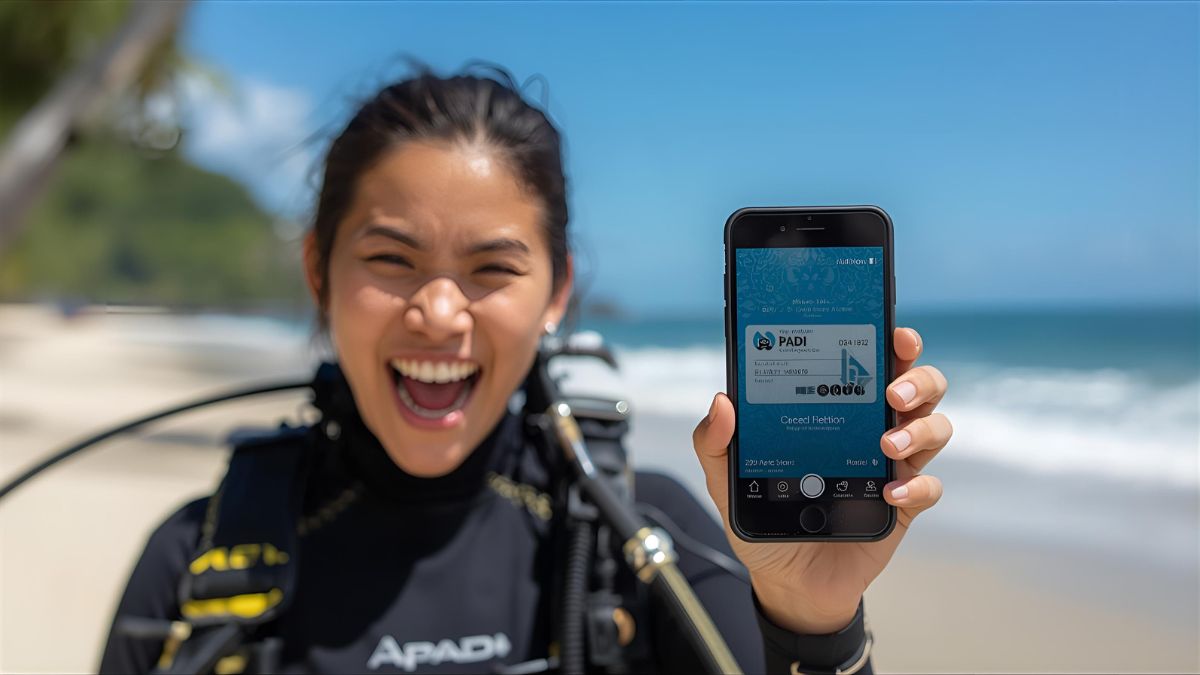

2. The Smartphone App

Apps like MySSI or PADI are great. They create beautiful charts and you can upload photos.

The Risk: Electronics fail. I have seen divers lose their phones in the ocean. I have seen apps crash or lose data after an update. If you rely 100% on the cloud, make sure you can access it offline when you are on a remote island with no WiFi.

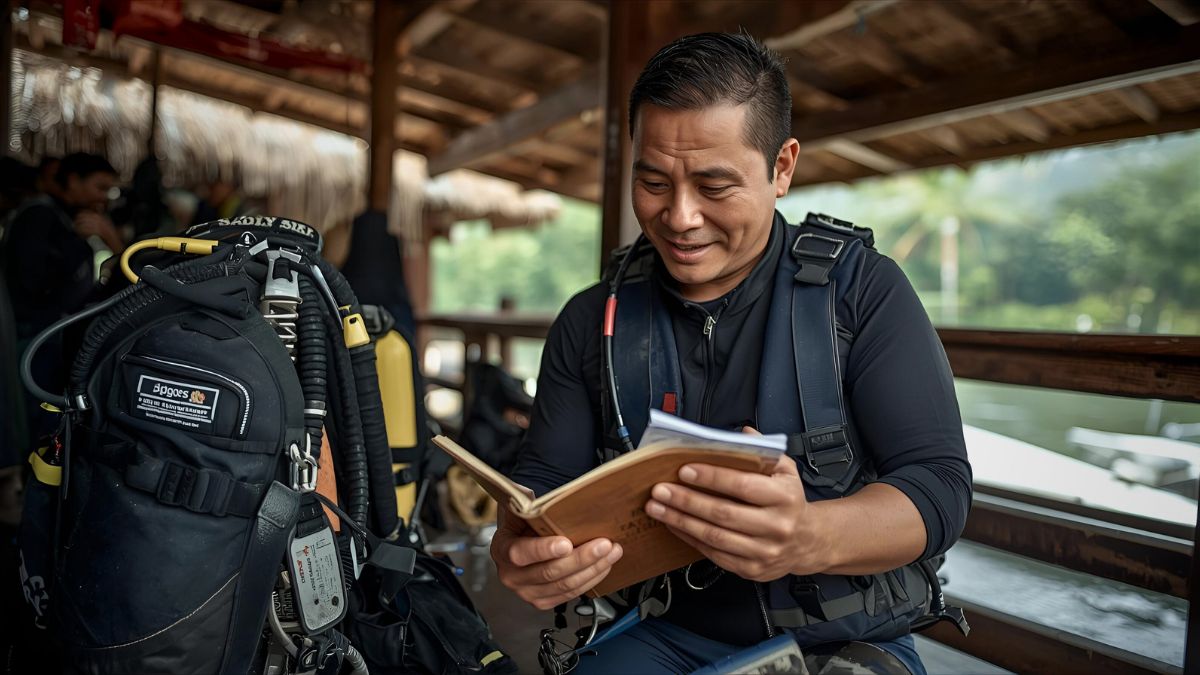

3. The Paper Logbook (The King of Reliability)

Call me old fashioned, but paper has advantages. It never runs out of battery. It doesn’t break if you drop it (unless into the water, but waterproof paper exists).

But the real value is the social aspect. Passing logbooks around after a dive, sharing stamps, and writing notes for each other builds community. A physical stamp from a dive center in Galapagos or the Red Sea is a souvenir that a digital badge cannot replace.

What You Should Actually Write (Stop Writing Novels)

Beginners often write essays: “Dear diary, today the water was blue and I felt happy.” That is sweet, but useless for your future self.

To make your logbook a tool, you need to record the variables that change. Here is the checklist I use for my own technical dives:

- Exposure Protection: Be specific. “5mm wetsuit” is not enough. Was it a new suit (buoyant) or an old one (compressed)? Did you wear a hooded vest?

- Tank Type: This is huge. An aluminum 11L tank becomes positively buoyant (floats) at the end of the dive. A steel 12L tank stays negative. This changes your weight requirement by 2-3 kg. Always write “AL” or “Steel.”

- Weight & Placement: Don’t just write “6 kg.” Write: “4 kg on belt, 2 kg in trim pockets.” This helps you find your perfect trim next time.

- Conditions: “Strong current from the North.” “Thermocline at 15 meters.” This helps you prepare mentally if you return to the same site.

- Gas Consumption: Did you finish with 50 bar or 100 bar? This helps you track your fitness and efficiency over time.

Advanced Logging: The SAC Rate (Level Up)

If you want to move from “tourist diver” to “expert,” use your logbook to calculate your SAC Rate (Surface Air Consumption). This is a number that tells you how much air you breathe per minute, normalized to the surface.

Why does this matter?

If you know your SAC rate (e.g., 15 liters/minute), you can plan dives accurately. You can look at a dive map, see that the average depth is 20 meters, and calculate exactly how long a standard tank will last you. You stop guessing and start planning.

You cannot calculate this if you don’t log your “Start Pressure,” “End Pressure,” “Average Depth,” and “Bottom Time” for every dive. Your logbook becomes a laboratory for your own physiology.

The Professional Path: You Can’t Pro without Logs

If you ever dream of becoming a Divemaster or Instructor, your logbook is a legal document.

To start the PADI Divemaster course, you need 40 logged dives. To become an Instructor, you need 100.

I have had students come to me wanting to turn pro, claiming they have “hundreds of dives,” but they stopped logging them at number 20. I cannot accept their word. PADI requires proof. They had to spend weeks diving just to get their numbers up on paper. Do not make that mistake. Even if you think you will never be a pro, keep the option open.

Comparison Table: Dive Logbook Types

Still undecided? Here is the breakdown of pros and cons.

| Method | Pros | Cons |

|---|---|---|

| Paper Logbook | No batteries, collects physical stamps, distinct proof of experience. | Can get wet/lost, takes physical space. |

| Mobile App | Auto-syncs, nice charts, geo-tagging, always in pocket. | Data loss risk, battery dependent, hard to stamp. |

| Dive Computer Memory | Accurate profile data, zero effort required. | Limited capacity (overwrites old dives), no context notes. |

Frequently Asked Questions

What happens if I lose my logbook?

It is heartbreaking, but it happens. If you lose it, try to reconstruct your recent history using your dive computer’s memory or contact the dive shops you visited (they usually keep records). Start a new one immediately. For professional courses, you might need to sign a statutory declaration of your experience.

Do I really need a stamp from the dive shop?

Technically, no. But the stamp adds verification. If you show me a logbook filled with your own handwriting and no stamps/signatures, I might be skeptical. A stamp from a recognized center proves you were actually there.

Can I just use my GoPro videos as proof?

Videos prove you were underwater, but they don’t prove the depth, time, or how many dives you did. They are great memories, but they are not a logbook.

When should I stop logging dives?

Never. I have over 5,000 dives, and I still log them. The format changes (I use digital software now for technical dives), but the habit remains. You never stop learning, so you should never stop logging.

The Dive Logbook: Your Underwater CV

Think of your logbook as your underwater CV (Curriculum Vitae). It tells the story of your progression from a nervous beginner to a confident explorer. It holds the data that keeps you safe and the memories that keep you inspired.

So next time you are on the boat and the Divemaster brings out the stamp, don’t roll your eyes. Take five minutes to write down the details. Your future self, standing on a boat in a different ocean, trying to guess how much weight to wear – will thank you.

Sources and References

- PADI – Guidelines on logging dives for training and experience verification.

- DAN (Divers Alert Network) – Importance of dive data for accident analysis and medical research.

- Scuba Diving Magazine – Tips on how to calculate Surface Air Consumption (SAC) rates.